Brad Steeg’s Seattle home was built in 1915, and from the description he provides in this post at GBA’s Q&A forum, it’s not hard to understand why Steeg is so uncomfortable during the winter: not much insulation, single-pane windows, and lots of air leaks.

“During the winter, my thermostat reads 70° but it still feel cold because the cold walls and ceiling suck the heat out of my body,” Steeg writes.

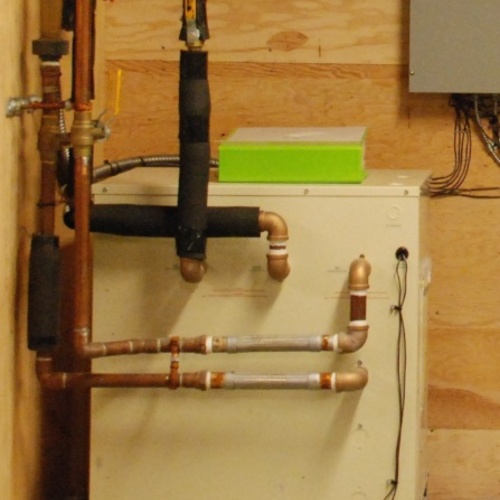

Exterior walls on the single-story, 900-square-foot house are framed with 2x4s. Steeg says some fiberglass batt insulation has been “stuffed in nooks and crannies” as previous owners opened up walls in the past. But the insulation is apparently spotty, and what’s there is dirty, indicating plenty of air gaps.

His plan is to add Tyvek housewrap, two layers of 2-inch-thick Roxul ComfortBoard 80 mineral wool insulation, 2×4 furring strips to create a rainscreen gap, and, finally, fiber-cement siding. Ceiling insulation will have to wait until an electrical upgrade in the future.

Steeg’s single goal is “comfort.” The question for this Q&A Spotlight is whether he’s on the right track.

Air-sealing before insulation

A continuous layer of insulation on the outside of the wall is typically a good idea, but adding insulation to a wall with lots of air leaks is putting the cart before the horse, suggests Dana Dorsett.

“Adding insulation over an air-leaky wall isn’t the best investment, since the air leaks can be anywhere,” Dorsett says. “Whether you add insulating sheathing or not, fixing the air leaks is the first order of business.”

One option would be to drill holes through the siding and sheathing (or removing a clapboard) and blowing in either cellulose or fiberglass from the outside of the house. That, Dorsett says, would “tighten things…

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

This article is only available to GBA Prime Members

Sign up for a free trial and get instant access to this article as well as GBA’s complete library of premium articles and construction details.

Start Free TrialAlready a member? Log in

6 Comments

Air temperature is the

Air temperature is the primary determinant of thermal comfort, but it's far more complex than that. Here is a tool to help:

http://www.healthyheating.com/solutions.htm

Ideally you would find someone who can present all of the upgrade options along with the cost effectiveness - including simply turning up the heat on colder days.

Sealed insulating sheathing

Wouldn't rigid foam sheathing with weather barrier and air sealing attention (either on structure, or on rigid insulation) address both the infiltration and thermal issues? An empty stud cavity represents no thermal disadvantage with enough outboard Rs and even as proposed, state code would have an interior vapor retarder optional.

Rigid foams (XPS or ISO) offer superior insulation, moisture resistance and, as stated, constructability.

RE Planning a Retrofit in the NW

From the story: "However, he wonders whether it would be safer to remove the drywall inside the house to insulate the wall cavities because in that case he would be able to check the wiring.

"That way I could remove all existing bat insulation (most likely incorrectly installed, just like it is incorrectly installed in the attic) and I can inspect the wiring," Steeg writes. "With an old house like this I don't want to do anything without seeing it first."

I live in the Seattle area, east side of Lake Washington. Houses that were built in Seattle during the era described were often knob and wire in the attic... sometimes upgraded by owners or DIY'ers over the years. Pulling the sheet rock off provides a far greater flexibility in making the house resilient and perhaps able to with stand for another 102 years.

First, The 1915's houses probably are not sheet rock, but are lathe and plaster. And you might find some rats inside the walls. If it is plaster, that may have been added on top of the lathe and plaster.. or it had been remodeled previously. Check with the city to see what permits had been previously pulled for the house. If it had been remodeled in the 70's and later then permits and inspections are probably in the city records and they may be able to help guide your priorities.

1. Checking the wiring is just one of the reason... (even if it had been upgraded in the 50's or early 60's) Occasionally in older houses in this area you can run across outlets that are ungrounded -- or a three prong outlet on a two wire system. There was a time in the 60's and 70's in which aluminum wire was pulled in houses... this gives a great opportunity to check for and correct that if necessary.

2, Old houses can have dead legs of water pipe that still attached to the active water lines - but capable of brewing bacteria... good time to spot those and remove with the sheet rock off.

3. Removing the sheet rock also allows better inspection of the structure from inside the house... addressing any dry rot that might have occurred over the years.

4. Earthquake hardening... yup we are in one of those areas that can have significantly stronger earthquakes than even some areas of southern California. With the sheet rock off - the structure can be attached to the foundation, made more rigid and able to handle the forces on it. In the area there are a number of companies that can handle the engineering of the house... having that sheet rock off speeds up the process and lowers the cost.

5. While the sheet rock is off - you can also look at the placement of switches and outlets adding new locations and removing old switches/outlets that just don't work for the house.

6. A 1915 built house is likely to have lots of lead paint, ceilings with "pop corn" texturing could contain asbestos.. so be prepared for additional work.

7 If you open up the walls - you may also discover some artifacts of historical value... like old Seattle Pilots banners, Olympia & Rainier beer bottles. Old newspaper from a century ago...

I prefer the Roxul comfort board to the other suggestions - but that's because I know that in some areas of Puget Sound the rain is driven pretty hard at times by the wind.. and it can swirl around. The mineral wool solution can take a soaking and not support mold... I've seen most of the foam products that get wet here support mold over time.

There was some mention of carpenter ants and foam... that could be managed in general with keeping the area around the house clean and landscaping away from the house. And if you've seen carpenter ants in the neighborhood its probably more important to look inside the walls to make sure that there hadn't been any structural compromise in years gone by.

Even though we live in the Seattle area (marine climate zone 4).. the area is actually reasonably dry. We saw that last summer with months without rain. Seattle area homes normally don't have a big problem with condensation on the outside walls (seldom drops much below freezing for any amount of time... and dew point isn't reached as often - unless the house has had bathrooms and kitchens venting into the walls. I've seen that done MULTIPLE times. You won't necessarily notice the problem and be able to fix it unless you have the inside wall cladding off.

I'd guess the big issue is do you have the time and the money to gut the house and fix problems that might be discovered?

Replacement Windows

I question the sustainability of replacement windows. How is manufacturing, shipping, installing new windows every 10-15 years more sustainable than restoring, weatherizing, and maintaining 1915 old wood, single pane windows and adding storms which last decades longer? Here is a calculation tool for such an assessment. https://www.hutchgov.com/1513/Cost-Comparison-Tool.

Response to Catherine Brooks

Catherine,

For more information on the issue you raise, see What Should I Do With My Old Windows?

attacking from the inside to keep original house vernacular

I understand wanting to attack this from the outside assuming you are living in the house, however I would love to see it done from the inside, leaving the outside architecture in place to better fit in the neighborhood. My plan would be to strip the interior down to the studs, fir them out to the equivalent of a 2x6, rewire the house, and reinsulate. with mineral wool or the material of your choice. From my perspective you don't live in a cold climate, so you'll never get a return on investment by going too aggressive in energy efficiency. Spray foam airseal around all your doors and window rough openings, whether or not you replace them. To share some other's concerns about your windows as well, I would not just jump to replacing the windows as a first option. Martin Holiday has written about the sense of this from a ROI strategy. I have to wonder if you wouldn't be fine by finishing your walls with a smart interior membrane and then your drywall. Replacing your lath and plaster with drywall is way less expensive than replacing all your exterior siding, especially if the effort is made to keep with the original vernacular.

Log in or become a member to post a comment.

Sign up Log in