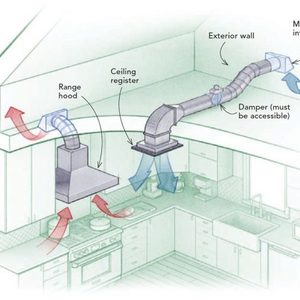

When Cheryl Morris moved into her new home, she realized that the kitchen exhaust fan was probably too powerful. Whenever she turned on the 1,200-cfm fan, strange things happened. “It pulled the ashes out of the fireplace, halfway across the room, right up to my husband’s chair,” she says. Those dancing ashes demonstrate an important principle: Large exhaust fans need makeup air.

The air that fans remove has to come from somewhere

Most homes have several exhaust appliances. They can include a bathroom fan (40 cfm to 200 cfm), a clothes dryer (100 cfm to 225 cfm), a power-vented water heater (50 cfm), a woodstove (30 cfm to 50 cfm), and a central vacuum-cleaning system (100 cfm to 200 cfm). The most powerful exhaust appliance in most homes, however, is the kitchen range-hood fan (160 cfm to 1200 cfm).

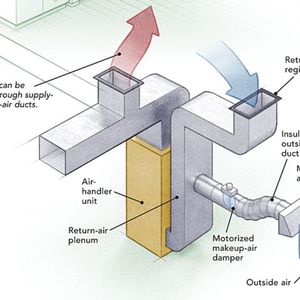

Although tightening up homes is a good way to make them more energy-efficient, builders need to remember that plugging air leaks makes it harder for air to enter a home. Every time an exhaust fan removes air from your house, an equal volume of air must enter. If a house doesn’t have enough random air leaks around windows, doors, and mudsills, makeup air can be pulled through water-heater flues or down wood-burning chimneys, a phenomenon called backdrafting. Because the flue gases of combustion appliances can include carbon monoxide, backdrafting can be dangerous.

One important way to limit backdrafting problems is to avoid installing a wood-burning fireplace or any atmospherically vented combustion appliance. Appliances in this category include gas-fired or oil-fired water heaters, furnaces, and boilers connected to old-fashioned vertical chimneys or flues. Instead, install sealed-combustion appliances with fresh-air ducts that bring combustion air directly to the burner. Most sealed-combustion appliances are practically immune to backdrafting problems.

Small exhaust fans—those rated at 300 cfm or less—usually don’t cause backdrafting problems. Anyone…

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

This article is only available to GBA Prime Members

Sign up for a free trial and get instant access to this article as well as GBA’s complete library of premium articles and construction details.

Start Free TrialAlready a member? Log in

23 Comments

Location of make-up air

If you are going to supply un-tempered make-up air, I wonder what difference there is in where it is located? A motorized damper and grill in the backsplash of the range might mitigate comfort and heat-loss concerns. Does anyone know if there has been any studies showing whether the proportion of air exhausted that comes from the vent, not the room, varies significantly based on it's location?

Response to Malcolm Taylor

Malcolm,

Ideally, the range hood exhaust fan will pull away the smoke and odors emanating from the stove. The problem with your backsplash idea, which has been tried, is short-circuiting: the exhaust fan often ends up pulling most of its air from the makeup air grille, allow the smoke from the roasting meat to drift into the kitchen.

Good Point

I still can't but think that a directed supply air could somehow be more efficient. Years ago I worked on a couple of high-tech manufacturing facility designs. Their air supply and exhaust was situated to take the contaminants produced directly out of the rooms without affecting the products being produced. The same is true of hospital operating rooms with their vertical air flows.

Someone with more ingenuity than me might come up with a solution.

Makeup air design

Martin - Although this is about commercial equipment, http://www.fishnick.com/ventilation/ventilationlab/ has some really good info, including some downloadable PDFs on this link on how to design effective makeup air systems. It addresses the short circuiting you mention as well. It would be nice to see this level of research on residential systems.

Providing Makeup Air (CEC and BSC Resources)

As a general warning on providing makeup air--in general, you want to let the warm plume of air rising off the cooking surface rise **into the hood** to be exhausted. Introducing lots of makeup air too close to this "plume" will disrupt it, and often result in worse capture efficiency. Even concepts that seem to make sense--like a "curtain" of air at the front of the hood--can result in disrupted airflow and worse capture efficiency. The less you disrupt the plume, the better it works.

There's a great report from the California Energy Commission using schlieren (flow visualization) images to show what's going on. It looks like it's the same (or similar) material that's in ASHRAE HVAC Applications.

http://www.energy.ca.gov/reports/2003-06-13_500-03-034F.PDF

Also, for those who want the entertaining version of kitchen exhaust a la Joe:

BSI-070: First Deal with the Manure and Then Don't Suck

http://www.buildingscience.com/documents/insights/bsi-070-first-deal-with-the-manure/

Why can’t range-hood exhaust ducts be designed to recover heat?

Just for folks' reference--in **commercial** kitchens, range hood heat recovery does exist--per the Environmental Building News cover story from February 2010. But I've never heard of it for residential. The story emphasizes just how hard of a problem it is to deal with cooking grease, per Martin's column.

Response to Kohta Ueno

Kohta,

Thanks for the useful links. And thanks for backing up my analyses of the problems associated with exhaust fan short-circuiting and gummed-up heat-exchange systems.

"Dynamic Relationships" = depressurization

Martin, your "dynamic relationships" seem to be a euphemism for, or maybe a distraction from, the depressurization that accompanies large exhaust and inadequate make up air. The code requires make up air for large exhaust to minimize depressurization. Designing for reduced exhaust due to small make up air openings seems to embrace depressurization as a solution to its own problem.

I like Broan's approach: give us really big (passive) openings. Once a designer contemplates the opening required to match the range exhaust, perhaps they'll consider reducing the size of the range fan.

Response to Brian Just

Brian,

My use of the phrase "dynamic relationship" was neither a euphemism nor a distraction. I am well aware of the problem of depressurization. Although the magazine editors at Taunton chose to omit most references to depressurization in this article, referring instead to backdrafting problems, there is no doubt that the entire focus of the article is on the problem of depressurization.

For a more extensive discussion of these issues, you can read the online article on which this magazine article was based: Makeup Air for Range Hoods. In that article, I wrote, "Since most residential kitchens are adequately served by a 150-cfm or 250-cfm range hood, it comes as no surprise that a 1,200-cfm range hood can cause depressurization and backdrafting problems."

I certainly don't recommend that readers design insufficient makeup air systems to "embrace depressurization," as you put it.

The dynamic relationship I discussed is a fact. It is based on physics; it is not a description of desirable outcome. As an exhaust fan ramps up, infiltration through cracks in the envelope increases. The change in the infiltration rate happens as a direct result of the depressurization caused by the exhaust fan -- not because a designer wants it to happen.

Gas cook tops vs. induction

It seems like one of the contributing factors in the make-up air issue is the choice of cook top. The commercial gas ranges that are all the rage produce huge amounts of heat and off-gas, and also have high ventilation requirements.

In the highly insulated home we are building, our HRV contractor recommends an induction cook top with small hood. When we need to turn on the ventilation system, we switch the boost on the HRV.

Any comments?

As usual, thank you in advance.

Response to Peter Whitman

Peter,

Like you, I prefer range hood fans to be small. As I wrote in the article, a range hood fan rated at 160 cfm to 200 cfm is a good way to go.

Peter

Another GBA article you may find interesting:

https://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/blogs/dept/green-building-news/hazards-cooking-gas

Gas vs. induction

Peter, yes, it is a good idea from an air-quality perspective to run a hood at least on low whenever you have a gas burner on. That probably negates the efficiency advantage of gas vs. electric, and now that we have the induction option, the combination of induction with a small (200 cfm or less) hood seems good. Then you only run the hood if the cooking is generating stuff you want to vent.

We are installing an HRV in our new home with an exhaust in the kitchen, but were told that can't replace a range hood. We're planning to have an electric cook stove and are wondering: Will a ductless range-hood will be sufficient combined with our HRV exhaust. Or are ducted range hoods the way to go with a lower CFM fan? (A separate but related question: How far should the HRV kitchen exhaust duct be from the stove to minimize grease?)

Thanks!

Ryan

We have a recirculating range hood, with an HRV exhaust in the kitchen. Works fine for us. I think about 8' is recommended for the setback. More important is to have a grease filter in the exhaust register. If you go this route, make sure you size e HRV to allow a boost mode. I.e., if your ventilation requirement is 100cfm, get an hrv that can do at least 150cfm, preferably 200cfm.

Ryan,

In areas where the local building code requires a range hood exhaust system, you may not be able to substitute a recirculating fan unless you get your plan approved by your local code authority.

That said, many Passivhaus builders routinely install a recirculating range hood (usually one with a special charcoal filter) in conjunction with an HRV exhaust grille elsewhere in the kitchen (about 6 feet or more away from the stove). This works, unless there is a cook in your family that does a lot of grilling and frying.

A recirculating fan in the kitchen works as well as a recirculating toilet!

Armando,

The trick is to just spray the ERV core with a bit of Febreze after cooking...

Ryan, you have brought up an interesting topic that seems to be ever-evolving. To Direct Vent or Not to Direct Vent? A recent study on indoor air quality of nine high performance homes in Colorado showed that balanced ventilation combined with a recirculating range hood might be inadequate. At least a handful of building scientist agree including Allison Bailes and John Straube, who Armando Cobo was quoting.

https://www.treehugger.com/kitchen-design/exhaustive-new-study-looks-kitchen-exhaust-and-household-air-quality.html

After over-thinking the topic myself, I decided to opt for balanced ventilation/recirculating range hood and heavy frying on the outdoor grill.

Interesting article, but a couple of things make me question the bias of this investigation. To wit:

"It should be noted that is a long time to cook a fried egg, and the emissions from this activity are likely higher than a normal fried egg. The goal was to produce substantial emissions that are within the range of normal cooking."

I don't know how anyone could write both of those sentences in the same article, let alone say them back to back. One literally contradicts the other. In whose estimation is burning food is "within the range of normal cooking"? Not mine. A more honest second sentence would have read "The goal was to produce a high level of emissions that would represent an extreme event in the kitchen, to really put these houses to the test."

It would have been a really good idea to also include a test of truly normal cooking. I kind of suspect the reason they didn't is because they had a predetermined goal of proving that an exhaust hood is required, and this test could have potentially gotten in the way of that. Much easier to burn an egg to a crisp and claim that is a normal cooking event.

There's also a weird anomaly in their data they make no acknowledgement of, or attempt to explain. In the majority of the passive houses, according to their data, the boost function increased the length of time there was poor air quality. The effect is much less apparent in the short term test, but still a couple of houses seemed to actually suffer from increasing the ventilation rate. The cases where there was initially a reduction in pollutants, but then took longer to drop below the target level are the most puzzling. This kind of unexpected result without any attempt to explain it calls into question the accuracy of the test method.

Trevor,

I agree. I think the 6 minute-egg-burn test was a bit superfluous. Furthermore, after such extraneous cooking events, one could conceivably just open a window for a little while- even in winter.

I think the test included utilizing the boost mode where it was available but I would have to double check.

I think people should do their due diligence to determine what works best for them. I opted for balanced ventilation with recirculated range hood but would have actually preferred direct vent from range. However, until a user-friendly, air-tight damper becomes available I will avoid direct vent due to comfort concerns.

I know this is an older article, but does anyone have recommendations on venting requirements for induction cooktops?

I have seen recommendations for 100 cfm per linear foot of cooktop and a more generic recommendation of 600 cfm. That is a fairly sizable difference for a 36 inch induction cooktop (300 vs 600 cfm) and greatly affects my make up air strategy. Thanks!

If it's for yourself, you can choose based on your cooking style. If you are doing a lot of high-temperature frying, you'll want more ventilation than if you like to gently simmer things. I think that 300 is probably plenty for most people, but if you buy a larger unit with a good multispeed fan (either ECM or an induction motor with switched windings), you can run it on 100 or 200 CFM most of the time but have 600 available when it's needed.

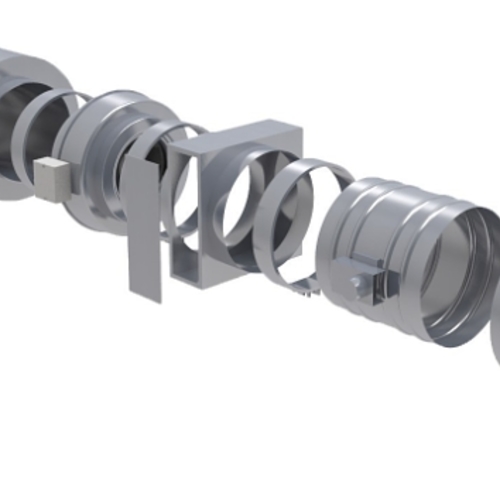

How come a motorized damper is always used/advised for makeup air, but nobody seems to use motorized dampers for the hood duct? It seems better for a tight home than a typical spring loaded backdraft damper. Is there a negative to a motorized one?

Log in or become a member to post a comment.

Sign up Log in